By Bethel Ogbeha

In the crowded Felele market in Lokoja, 52-year-old Alhaji Musa Ibrahim, bends over a half-finished pair of leather sandals, his hammer rising and falling in practiced rhythm. For thirty-five years he has sat here, turning hides into footwear that Kogi people proudly wear to churches, mosques, and naming ceremonies. But these days the rhythm is slower, the smiles fewer.

“Business is hard,” he says, wiping sweat from his brow. “Everything has gone up—glue, sole rubber, thread, even the small nails. But the price we sell cannot follow because people don’t have money. And government? We don’t see them.”

Alhaji Musa is not alone. From Okene to Ankpa, Idah to Kabba, thousands of shoemakers and leather artisans are feeling forgotten by the same State Government that regularly announces multi-billion-naira projects and empowerment schemes for women and youths.

Pending Promises

Two months ago, traders and market women in Lokoja were invited to a town-hall meeting with the Commissioner for Commerce and Industry. Photographs of smiling women clutching forms for “incoming soft loans and grants” flooded social media. Shoemakers heard about it too, but no one called them.

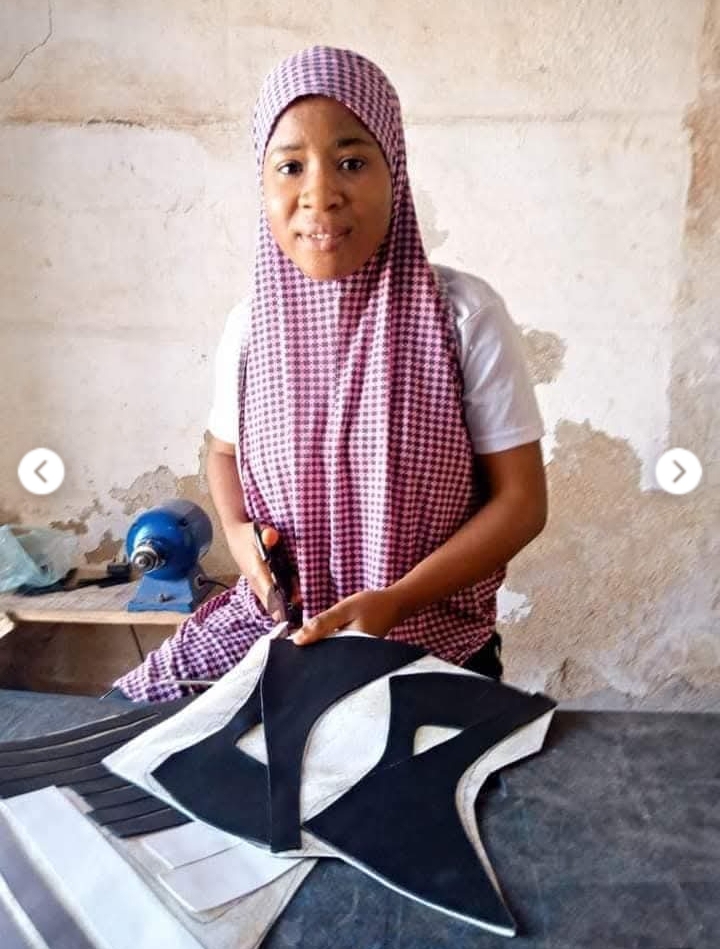

“We registered with the ministry years ago,” says Blessing Okpanachi, a 28-year-old female cobbler in Ganaja village who learned the trade from her late father. “They have our names, our cluster locations, even our phone numbers. Yet when they share anything, it is for rice sellers, tailors, or hairdressers. Shoemakers are never remembered.”

The result is stark. While some trader groups speak of “programmes in the pipeline,” shoemakers say they have received zero targeted grants, zero low-interest loans, and zero training on modern designs or machinery.

Taxes That Bite Deeper Than Hammers

A 2024 survey by the Kogi State Artisan Network revealed that small-scale manufacturers in the state pay effective tax rates as high as 18–22% of turnover when multiple levies from local government, state revenue service, and market authorities are combined. For many shoemakers operating on margins of 15–20%, this is simply unsustainable.

“Every month they come with tickets,” complains Suleiman Abdullahi in Okene. “Signboard tax, sanitation tax, business premises tax, even something called ‘security levy’. If you don’t pay, they lock your shop. How can we grow like this?”

The burden forces difficult choices: buy cheaper, lower-quality materials that wear out fast and damage reputation, or raise prices and watch customers drift to imported Chinese shoes sold for next to nothing in the same markets.

Roads That Ruin Leather

In Ejule and Alla in Ofu Local Government, clusters of shoemakers rely on tanneries in Kano and Aba for treated leather. But the deplorable state of the Alla-Ejule-Otukpo federal road means lorries spend days instead of hours, and rain often soaks consignments worth hundreds of thousands of naira.

“Last month I lost almost ₦280,000 because the leather got wet inside the truck,” says Emmanuel Ojochu, secretary of the Ejule Shoemakers Cooperative. “When we complain, they tell us the road is federal. But federal or state, it is our leather that is being ruined”

What Shoemakers Want

Across the state, artisans have reduced their demands to four straightforward requests:

1. Tax relief or total exemption for registered micro-producers earning below a certain threshold.

2. Dedicated micro-finance windows with single-digit interest rates and little or no collateral, channeled through their existing clusters.

3. Regular skills upgrade programmes in partnership with the state’s vocational centers, focusing on modern footwear design, machine maintenance, and use of eco-friendly materials.

4. Guaranteed stalls and visibility at Kogi Trade Fairs and the yearly Lokoja International Market exhibitions, plus improvement of feeder roads linking production clusters to highways.

“We are not asking for handouts,” insists Hajiya Ramatu Yusuf, Chairperson of Ankpa Women Leather Workers Association. “Give us small loans at 5% or 6%, train us once or twice a year, reduce the multiple taxes, and fix the roads so our goods reach markets on time. We will do the rest ourselves.”

A Cultural Heritage at Risk

Shoemaking in Kogi is more than a job; it is an identity. Ebira brides wear hand-crafted leather slippers embroidered with traditional motifs. Igala kings commission special sandals that only master craftsmen in Idah can produce. When these artisans fold up, a piece of the state’s soul disappears.

As evening falls over Okkabiri market in Ganaja, the glow of small kerosene lamps illuminates rows of tired but determined faces still bent over lasts and awls. They will be here tomorrow, and the day after, stitching not just shoes but survival.

Until Kogi State Government decides that these everyday craftsmen deserve the same attention it gives to ribbon-cutting ceremonies, the sound of hammers on leather will continue to echo a silent question:

When will our turn come?